A man goes to see his optician and asks for a pair of reading glasses.

The optician: I already gave you a new pair last week.

The man: I have already read them.

Text-ures 3

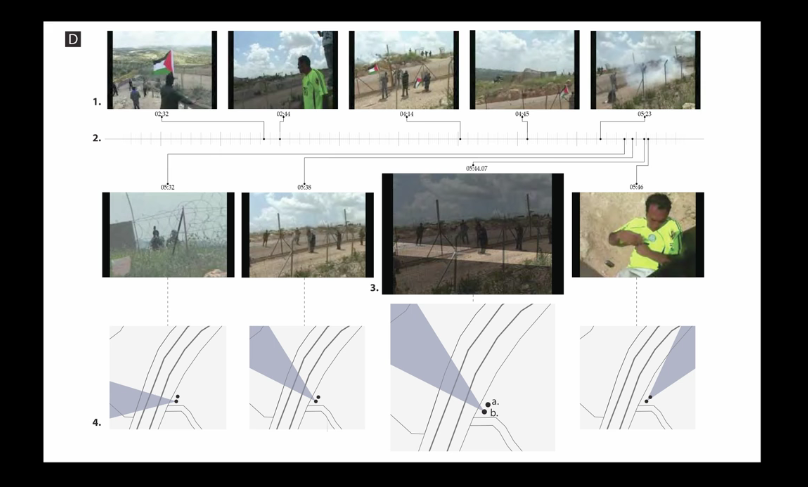

Forensic Architecture

Dump of notes taken during the presentation of Eyal Weizman at the the seminar Culture@Work

What is an evidence? How to socialize it?

Text-ures 2

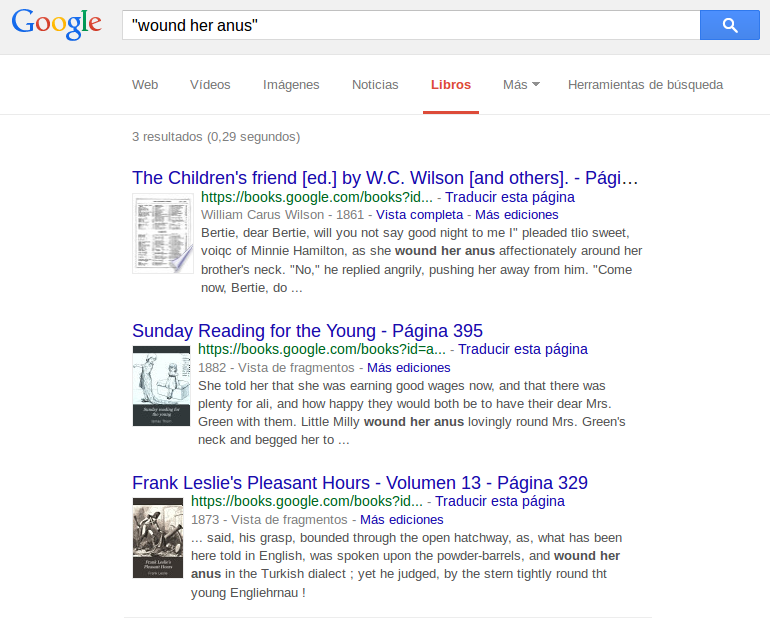

Lapsus by the Google Books OCR program. The visual approximations of the algorithm for the word arms and anus are similar enough to create some confusion. Mentioned by Nanna Bonde Thylstrup in her talk The politics of archival assemblages in the seminar Culture@Work

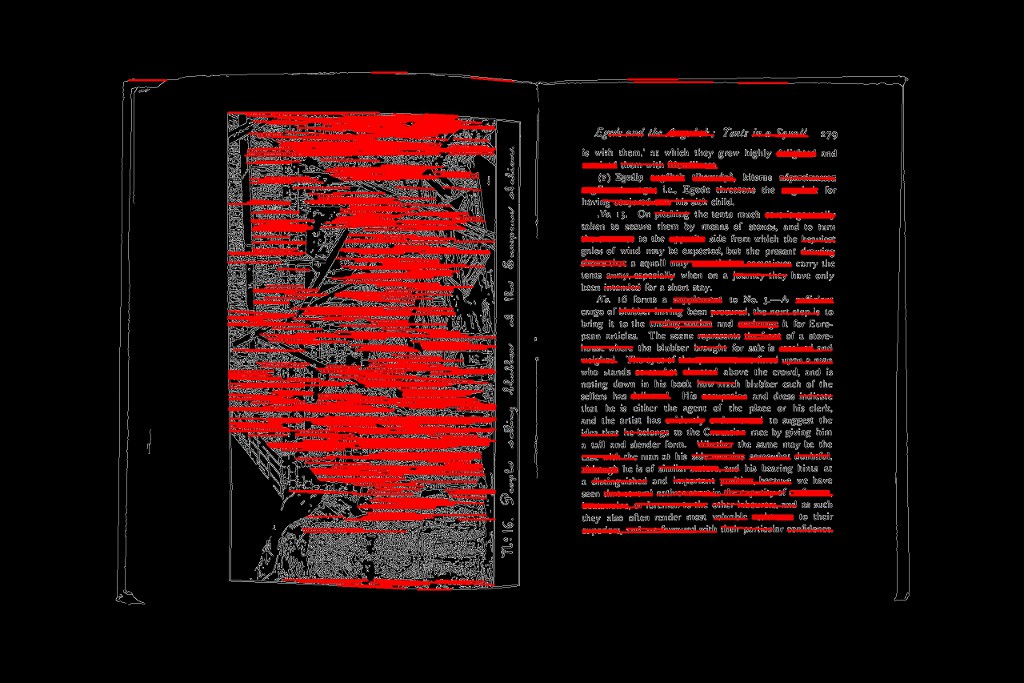

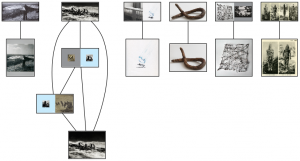

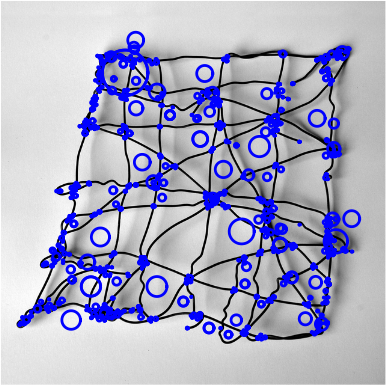

SIFTing through the pages of ARKIV

A book in one sense is an ordering of a set of images. Here, a probe to consider how the layout of a book could be used to (reconstruct) an ordering of its original constituent images using SIFT feature detection.

Two species of bits

A digital universe – whether 5 kilobytes or the entire internet – consists of two species of bits: differences in space and differences in time. Digital computers translate between these two forms of information – structure and sequence – according to definite rules. Bits that are embodied as structure (varying in space, invariant across time) we perceive as memory, and bits that are embodied as sequence (varying in time, invariant across space) we perceive as code. Gates are the intersections where bits span both worlds at the moments of transition from one instant to the next.

George Dyson, Turing’s Cathedral.

The Book as Diagram

“People say that nobody knows what a book is any more. It is observed that people sit on trains, or buses and in waiting rooms and where a few years ago they would have been reading a book, they will instead be consoled at their phone doing some data processing. This might be the case, but perhaps no one has ever really known what a book is, because the book has always been changing. Today the book is again bursting its bounds, becoming a point of mediation, swallowing other media systems and forms of knowledge while fragmenting and migrating into new forms.

[…]

The gradient is a net we throw out to sea

“But classical science clung to a feeling for the opaqueness of the world, and it expected through its constructions to get back into the world. For this reason it felt obliged to seek a transcendent or transcendental foundation for its operations. Today we find—not in science but in a widely prevalent philosophy of the sciences—an entirely new approach.

Constructive scientific activities see themselves and represent themselves to be autonomous, and their thinking deliberately reduces itself to a set of data-collecting techniques which it has invented. To think is thus to test out, to operate, to transform—the only restriction being that this activity is regulated by an experimental control that admits only the most “worked-up” phenomena, more likely produced by the apparatus than recorded by it.

Whence all sorts of vagabond endeavors. Today more than ever, science is sensitive to intellectual fads and fashions. When a model has succeeded in one order of problems, it is tried out everywhere else. At the present time, for example, our embryology and biology are full of “gradients.” Just how these differ from what classical tradition called “order” or “totality” is not at all clear. This question, however, is not raised; it is not even allowed. The gradient is a net we throw out to sea, without knowing what we will haul back in it. It is the slender twig upon which unforeseeable crystalizations will form. No doubt this freedom of operation will serve well to overcome many a pointless dilemma— provided only that from time to time we take stock, and ask ourselves why the apparatus works in one place and fails in others. For all its flexibility, science must understand itself; it must see itself as a construction based on a brute, existent world and not claim for its blind operations the constitutive value that “concepts of nature” were granted in a certain idealist philosophy. To say that the world is, by nominal definition, the object x of our operations is to treat the scientist’s knowledge as if it were absolute, as if everything that is and has been was meant only to enter the laboratory. Thinking “operationally” has become a sort of absolute artificialism, such as we see in the ideology of cybernetics, where human creations are derived from a natural information process, itself conceived on the model of human machines. If this kind of thinking were to extend its dominion over humanity and history; and if, ignoring what we know of them through contact and our own situations, it were to set out to construct them on the basis of a few abstract indices (as a decadent psychoanalysis and culturalism have done in the United States)—then, since the human being truly becomes the manipulandum he thinks he is, we enter into a cultural regimen in which there is neither truth nor falsehood concerning humanity and history, into a sleep, or nightmare from which there is no awakening.”

Eye and Mind, Maurice Merleau-Ponty

The Primacy of Perception, ed. James M. Edie, trans. Carleton Dallery, Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1964.

Scanscape

A scan is not a photograph. The scanner head is like a comb of light-emitting fingers that slowly strokes its subject in order to see it. The final image denies this temporality in its conventional single and simultaneous presentation. This probe attempts to reintroduce the temporality of the scanner.

![]()