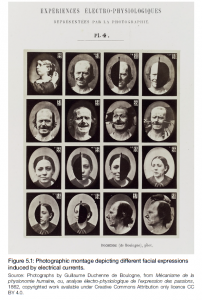

Duchenne was based at the Salpêtrière hospital in Paris, where he researched muscular electrophysiology—the perceived electrical dysfunction underlying neurological conditions, ranging from strokes and epilepsy through to the more questionable areas of hysteria and insanity. […] The afflictions of the inmates of the Salpêtrière made them perfect candidates for Duchenne’s research and documentation: muscular paralysis and facial anaesthetics made them extremely malleable. The flow of sustained electrical currents allowed Duchenne to overcome the limits of photography’s then long shutter speeds to have his sitters ‘hold’ a pose for an extended period. As Prodger notes:

Instead of accelerating the photographic process to produce instantaneous images, as others had tried to do, Duchenne devised a system for freezing the activity of his subjects long enough to accommodate the lengthy exposure times. (Phillip Prodger, Darwin’s camera: Art and photography in the theory of evolution, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2009, pp. 81-82)

In calibrating the speeds of his subjects to the speed of the technology, Duchenne reveals a moment that moves beyond Darwin’s fleeting emotions; while the expressions are undeniably involuntary, they are difficult, as Darwin discovered, to classify with any certainty. His electrical probes enabled him to isolate and control the appearance of various fluxes of emotional states yet always out of context of any real event.

Michele Barker and Anna Munster: “The Mutable Face“. In Imaging Identity: Media, memory and portraiture in the digital age, edited by Melinda Hinkson, published 2016 by ANU Press, The Australian National University, Canberra, Australia.