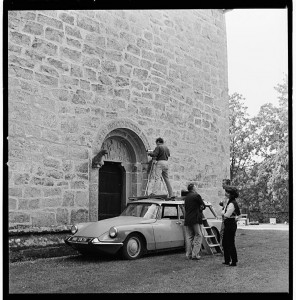

The Scandinavian Institute of Comparative Vandalism at work. Taken by Franceschi on Gotland in 1964, the photo shows Jacqueline de Jong, Asger Jorn, Ulrik Ross (on the roof of the Citroën) and an uidentified fourth man.[/caption]

The Scandinavian Institute of Comparative Vandalism at work. Taken by Franceschi on Gotland in 1964, the photo shows Jacqueline de Jong, Asger Jorn, Ulrik Ross (on the roof of the Citroën) and an uidentified fourth man.[/caption]

Ellef Prestsæter: Did you feel that you were collecting evidence for a specific archaeological argument?

Jacqueline de Jong: Yes, sure! It was the argument that there had been people, like the Visigoths, travelling all over the globe. Jorn wanted to show that the images are the same in Italy, Spain, Portugal, wherever you go.

So this was the comparative component of the project?

Yes, to show the comparative imaginary. We wanted to make these facts available through the photographs. This is, after all, what the Institute was about.

It is interesting that the project would begin in France and Spain, not Scandinavia.

Why? Why would you say that?

Because the Institute of Comparative Vandalism was said to be Scandinavian.

Well, do not take the name too literally. There’s a joke in there.

Sure, but it is also true that one of the planned outputs of the Institute was a multivolume book series on 10,000 Years of Nordic Folk Art.

Absolutely, and that was not a joke. Yet the folk art in question was not only Nordic, but spread all over the world.

Exactly, that’s why I think it’s interesting that you started outside of the Nordic countries, deconstructing the narrative about an inherently Nordic culture from the beginning. It also implies that the Institute cannot be reduced to the10,000 Years of Nordic Folk Art book project. There was more at stake.

Yes, and after all we were living in France, so it was logical to begin there. Later we went to Spain, Italy, Switzerland and Scandinavia. I think everything is okay with the name of the Institute, except “Scandinavian”, because that implies a limitation. It should have been the Institute of Comparative Vandalism, quite simply. Still, and this is important: the opposition between the North and the South of Europe was a hang-up of Jorn. He wanted to emphasise that a lot of culture had travelled south from the north, and not only the other way around, which was still a hegemonic archaeological idea in the Christian and Greco-Roman-oriented countries.

How would you describe the whole concept and project of the Institute?

It was such a big and perhaps even utopian project that you couldn’t imagine the whole thing being realised. However, travelling and doing the hands-on work was so enjoyable that you would forget about the 25,000 pictures that eventually got made. It was something of a snowball effect: you start, then through one thing you discover the next, and through the travelling, the comparative aspect of the project becomes more and more important and gets its form. So there you are. I don’t think there ever was a document specifying what was to be done. It was all very intuitive, and that is what made it so beautiful.

Excerpt from an interview published by Kunstkritikk. Read full interview here.