From http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/history/hooke.html

Hooke’s reputation in the history of biology largely rests on his book Micrographia, published in 1665. Hooke devised […] one of the best such microscopes of his time, and used it in his demonstrations at the Royal Society’s meetings. With it he observed organisms as diverse as insects, sponges, bryozoans, foraminifera, and bird feathers. Micrographia was an accurate and detailed record of his observations, illustrated with magnificent drawings […] It was a best-seller of its day. Some readers ridiculed Hooke for paying attention to such trifling pursuits: a satirist of the time poked fun at him as “a Sot, that has spent 2000 £ in Microscopes, to find out the nature of Eels in Vinegar, Mites in Cheese, and the Blue of Plums which he has subtly found out to be living creatures.” More complimentary was the reaction of the diarist and government official Samuel Pepys, who stayed up till 2:00 AM one night reading Micrographia, which he called “the most ingenious book that I ever read in my life.”

From Micrographia:

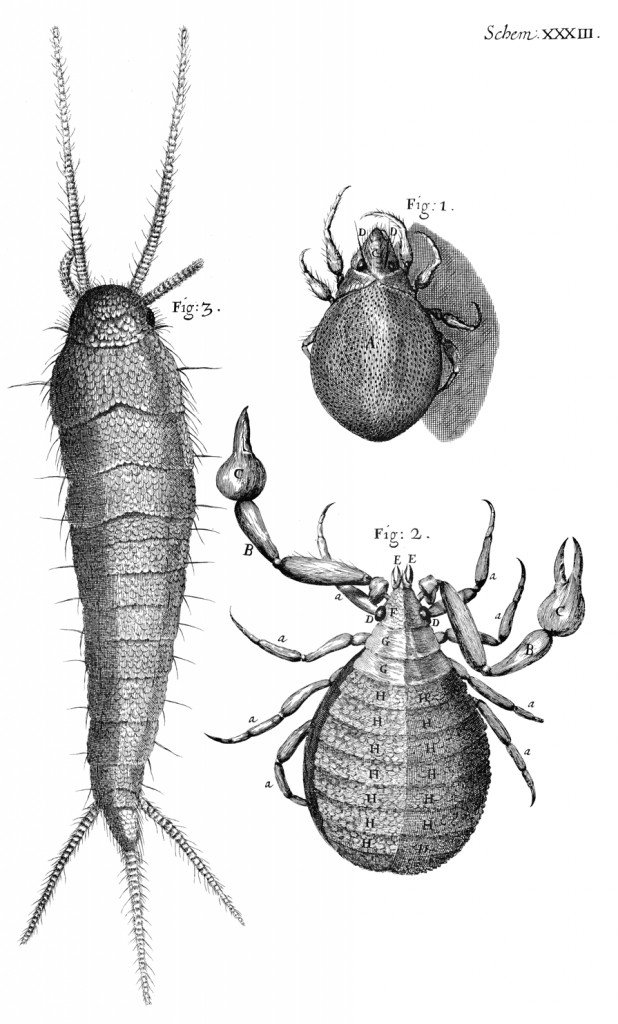

Observ. II. Of the small Silver-colour’d Book-worm.

As among greater Animals there are many that are scaled, both for ornament and defence, so are there not wanting such also among the lesser bodies of Insects, whereof this little creature gives us an Instance. It is a small white Silver-shining Worm or Moth, which I found much conversant among Books and Papers, and is suppos’d to be that which corrodes and eats holes through the leaves and covers; it appears to the naked eye, a small glittering Pearl-colour’d Moth, which upon the removing of Books and Papers in the Summer, is often observ’d very nimbly to scud, and pack away to some lurking cranney, where it may the better protect itself from any appearing dangers. Its head appears bigg and blunt, and its body tapers from it towads the tail, smaller and smaller, being shap’d almost like a Carret.

This the Microscopical appearance will more plainly manifest, which exhibits, in the third Figure of the 33. Scheme, a conical body, divided into fourteen several partitions, being the appearance of so many several shels, or shields that cover the whole body, every of these shells are again cover’d or tiled over with a multitude of thin transparent scales, which, from the multiplicity of their reflecting surfaces, make the whole Animal appear of a perfect Pearl-colour.

[…]

The small blunt head of this Insect was furnish’d on either side of it with a cluster of eyes, each of which seem’d to contain but a very few, in comparison of what I had observ’d the clusters of other Insects to abound with; each of these clusters were beset with a row of small brisles, much like the cilia or hairs on the eye-lids, and, perhaps, they serv’d for the same purpose. It had two long horns before, which were streight, and tapering towards the top, curiously ring’d or knobb’d, and brisled much like the Marsh Weed, call’d Horse-tail, or Cats-tail, having at each knot a fring’d Girdle, as I may so call it, of smaller hairs, and several bigger and larger brisles, here and there dispers’d among them: besides these, it had two shorter horns, or feelers, which were knotted and fring’d, just as the former, but wanted brisles, and were blunt at the ends; the hinder part of the creature was terminated with three tails, in every particular resembling the two longer horns that grew out of the head: The leggs of it were scal’d and hair’d much like the rest, but are not express’d in this Figure, the Moth being intangled all in Glew, and so the leggs of this appear’d not through the Glass which looked perpendicularly upon the back.

This Animal probably feeds upon the Paper and covers of Books, and perforates in them several small round holes, finding, perhaps, a convenient nourishment in those hulks of Hemp and Flax, which have pass’d through so many scourings, washings, dressings and dryings, as the parts of old Paper must necessarily have suffer’d; the digestive faculty, it seems, of these little creatures being able yet further to work upon those stubborn parts, and reduce them into another form.

And indeed, when I consider what a heap of Saw-dust or chips this little creature (which is one of the teeth of Time) conveys into its intrals, I cannot chuse but remember and admire the excellent contrivance of Nature, in placing in Animals such a fire, as is continually nourished and supply’d by the materials convey’d into the stomach, and fomented by the bellows of the lungs; and in so contriving the most admirable fabrick of Animals, as to make the very spending and wasting of that fire, to be instrumental to the procuring and collecting more materials to augment and cherish it self, which indeed seems to be the principal end of all the contrivances observable in bruit Animals

Impossible to resist showing the fantastic illustration of

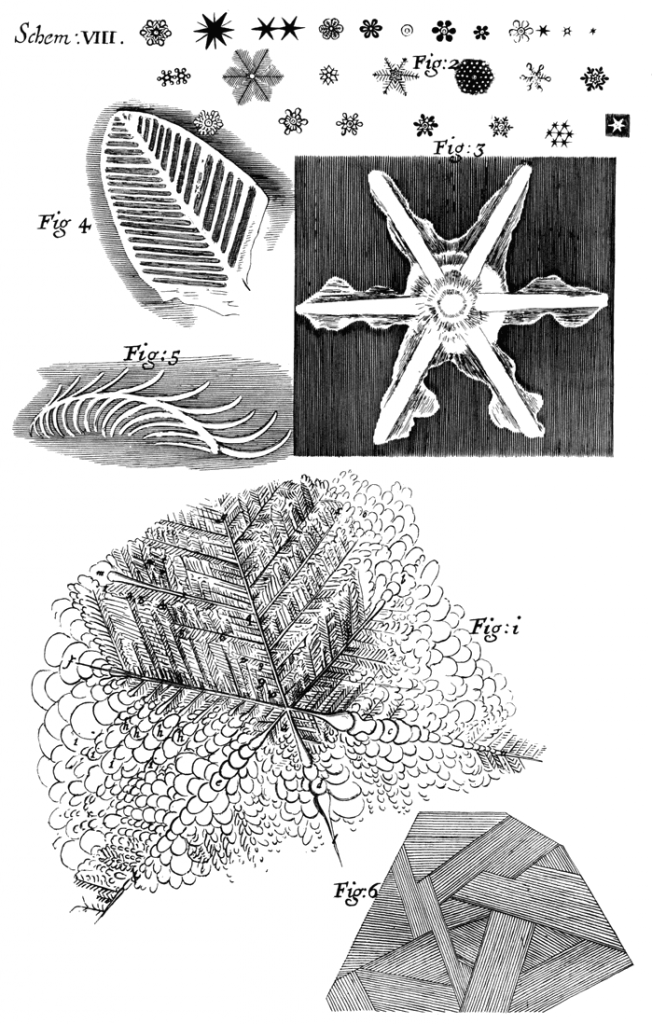

Several Observables in the six-branched Figures form’d on the surface of Urine by freezing.